The Principles of Yin

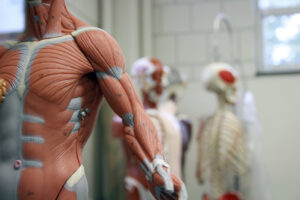

Physically, Yin Yoga targets the tissues below the waist. We want to be relaxed throughout our Yin practice yet hold strong focused awareness of our intention. Our focal point during these lengthy seated postures is the body’s connective tissue, particularly around the joints where the ligaments attach bone to bone. We do not target the muscles in Yin Yoga. Skeletal and anatomical variation is important in Yin Yoga; we must always modify postures to fit the individual as no two individuals are born with the same bone structure.

All forms of physical exercise use healthy stress to compress, stretch or twist various tissues in the body. Yang tissues (muscles, blood and skin) are more elastic and respond well to the rhythmic and repetitive heat producing yang styles of Yoga – power, ashtanga, and vinyasa. Yin tissues are drier and more plastic. Ligaments, bones, tendons and connective tissue need slow, gentle pressure delivered steadily in stillness for longer periods. While we can distinguish between yin and yang tissues to customize and refine our practice, they are continuous in the body: interconnected and always working together.

Connective tissue, also known as fascia, is the mysterious netting – made mostly of collagen – that holds us together in one piece: binding and aligning muscles and organs – allowing muscles to stretch and change shape. Yin puts pressure on the connective tissue and stimulates the production of collagen, elastin and Hyaluronic acid. One molecule of Hyaluronic acid can attract and hold 3,000 times its weight in water! There is amazing scientific research behind fascial discovery and if Dr. Motoyama’s insights are correct “then what textbooks have been calling connective tissue is in fact a living matrix that conducts life giving energy to every tissue, cell, and organ in the body.”

The Principles of Yin

- Come to your own healthy, intelligent edge. You know best, as you are your best Teacher.

- Find the stillness and resolve to be still.

- Hold the pose – anywhere from 1 – 10 minutes.

- Exit slowly. Allow yourself time to be vulnerable as you bounce back.

Because the very essence of Yin is a patient yielding surrender to the slow opening of deeper, stiffer tissues, it is crucial to go inside and listen, really listen, to your body and ground down. Yin is the perfect place for conscious breathing and an acute awareness of bodily sensations and mental and emotional fluctuations. Meditation is weaved throughout the Yin practice and we become the observer, we watch without becoming involved. Whatever may come up, we make contact and in that same moment we let go. Non-attachment provides us with the peace of knowing we have everything we need within.

We can see all around us a cultural preference for the Yang qualities of heat and speed. Exploring the cool, slow, lunar landscape of Yin brings balance into our practice and our lives. We will most certainly encounter discomfort at our edge – but never pain. This discomfort will challenge the ego mind – always seeking entertainment and distraction. A commitment to stillness lets time work its’ magic and in time magic moves and dissolves the edge. We open, and go deeper.

Yin Tissues and Yang Tissues ~ the difference.

As Yoga Practioners it’s important we clearly define what form (asana) we are teaching and more importantly WHY.

Yin tissue is much drier and much less elastic than the more supremely nourished yang connective tissue of muscles.

Begin looking at muscles like elastic (yang) and ligaments and tendons like plastic (yin). This will give you a better foundational outlook to why long, reasonable (not always comfortable) amounts of tension can reshape, reform, heal and revitalize specific areas of the human body. One of the muscles ‘jobs’ is to protect joints from hyperextending. If there’s too much stress on the joint, the muscle will tear (strain) then the ligaments (sprain) then finally the joint may become damaged. This is why your role as the practioner is important to align your students and engage the muscles correctly in a yang practice. In yin yoga, alignment is not imperative to the practice. In fact, it can create joint compression causing longterm damage to joints.

Stress versus Stretch ~ the difference.

We need to define a couple of important terms you’ll be using as part of your languaging as a yin practitioner. Techincally ‘stress’ is the tension we place upon our tissues while stretch is the elongation resulting from stress. A stretch doesn’t always accompany stress. There are four types of stretching of connective tissue (muscular)

- Dyanmic

- Ballistic

- Static

- Passive

Stressing the joints, ligaments and tendons is different to stretching the muscles.

Stress is Yin

Stretch is Yang.

Going deeper ~ The 5 Major Systems of Yin

There are five main systems in Daoism. They are sometimes contradictory and confusing but let’s simplify them.

- Magical Daoism is practiced widely around the world today working with the powers of natures elements and spirits. These are invoked and channeled through practioners to gain balance, health wealth and progeny.

- Divinational Daoism is based on the understanding the way of the universe is seeing the greater patterns of life living in harmony with universal forces. Divination Daolism utilizes the study of the stars and patterns found on earth to help us live harmoniously.

- Ceremonial Daoism was originally a spiritual practice. Unlike yoga which remained a personal spiritual practice, this system evolved into a religion.

- Action and Karma Daoism is taught through the value of proper behaviour and morality results in rewards both in this life and the next.

- Internal Alchemy Daoism is the practice that ‘chi’ becomes recognized as the key to health and a long life. Chi is gathered, nurtured, and circulated through a very strict practice.

The Daoists use terms that we do not use in the west. Words like ‘blood’ is replaced by ‘meridians’, bone exercises is called, ‘bone-washing’. We will stick to modern yinster terminology, up to date anatomy and physiology.

When to Practice Yin

There are absolutely no absolutes. The question of when to practice yin has no one single answer. There are many options for when to practice depending on what we would like to achieve thorugh our practice. As always, it comes down to intention.

We could practice yin when:

- Our muscles are cool. The benefits of yin on a cold body is the stress can travel deeper into ligaments and tendons rather than muscles.

- Early in the morning is when muscles are coolest.

- Later in the evening to calm the mind before sleep.

- Before an active yang practice to prepare the body for vigorous movement.

- During the warmer months of spring and summer to balance the environmental yang energy.

- After a long road trip or sitting for long periods of time.

- During a woman’s menstrual cycle to conserve energy.

It’s good to set an intention prior to any yoga practice to maximise the psychological benefits. Another intention may be to work into our joints and connective tissue or to maximise the emotional or spiritual practice.